|

|  |

|

"Keats/ and Light"

by Diane di Prima

pp 13-37, in Talking Poetics from Naropa Institute:

Annals of the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodies Poetics,

Volume One,

Edited by Anne Waldman and Marilyn Webb

Shambhala, Boulder & London, 1978.)

Left: poet Diane di Prima

June 24, 1975, Boulder Colorado-- The actual stuff that poetry is made out of is light. There are poems where the light actually comes through the page, the same way that it comes through the canvas in certain Flemish paintings, so you're not seeing light reflected off the painting, but light that comes through, and I don't know the tricks that make this happen. But I know they're there and you can really tell when it's happening.and when it's not. So I've been rying to figure out what makes it happen.And I think it's not very different from the light of meditation. So that I'm beginning to suspect that what makes it happen is the way the sound moves in you, moving your spirit in a certainway to produce a certain effect which is like the effect of light.

And I want to read to you something about the way sound moves in you, the way the sound moves in the hearer. It's from the second book of Natural and Occult Philosophy by Cornelius Agrippa in the 1400's. In the second volume of this three-volume work, Agrippa gets a lot into numbers. When he gets into numbers, he gets into music. When he gets into music, he gets at one point into the fact that vocal music is the most effective of all musics for moving the hearer. And what he has to say about vocal music. And what he has to say about vocal music is not that very different from the effects of a well-read, well-chanted poem:

Singing can do more than the sound of an instrument, inasmuch as it, arising by an harmonial consent, from the conceit of the mind and by imperious affection of the fantasy and heart, easily penetrateth by motion, with the refracted and well-tempered Air, the Aerious spirit of the hearer, which is the bond of soul and body, and transferring the affection and mind of the Singer with it, it moveth the affection of the hearer by his affection, and the hearer's fantasy by his fantasy, and mind by his mind, and striketh the mind, and striketh the heart, and pierceth even to the inwards of the soul, and by little and little, infuseth even dispositions; moreover, it moveth and stoppeth the members and the humors of the body . . . He goes on to say that breath is, of course, spirit, and that what happens is that the spirit, your spirit as a person singing or chanting or reading aloud, enters the ear and mingles in the body of the hearer, with his spirit, and so moves and changes the body's humors and dispositions. What we are is nothing but a physical instrument, not much different than a musical instrument in some ways, and the effect that we produce--or perceive--of light or other really high energy--meditative high--comes only out of changes in this physical instrument.

And so there is a way, to me, is that the most high aim of poetry is to create that sense of light. There are passages in the Cantos that do that. There are poems in every language that do it, and it's a question of some real subtle juxtapositions of vowels. Pound tried to track it down when he talked about the tone leading of vowels and harmonizing the different vowels, and Duncan is into that when he talks about assonance and "rhyme". Like picking up the same vowel over and over for a long time, and then changing it. Or paced--spaced--repetition of sound. Pound tried earlier to get at it when he wrote--in his critical essays-that we've always in recent centuries had a stressed beat in English verse, whereas the older, quantitative verse, where some syllables are more drawn out than others, gives more the sense of music. It also gives more the space for that phenomenon of light to occur.

One thing that I have just a glimmer, have a handle on, that I really think may be worth thinking about, is this phenomenon of light, in all, maybe in all arts. How it could suddenly burst into light in you body, if it does.

Another really separate thing that I wanted to do today is to share some passages of the letters of John Keats with you. Passages about the writing of poetry. They were maybe my earliest information on what poetry was about. Just like the most recent information I have is this of the breath and light, for me the earliest information was this that I want to read to you next. When I was a youngster, I had been reading a lot of Western philosophy and novels and came upon in a book, a novel by Somerset Maugham, a quotation from Keats. And then I pursued finding Keats and discovered there was poetry and wondered why anybody did it with philosophy when they could do it in a poem. And you can do it different in a poem every day, you can make a different construct. You can make a different reality every day instead of sticking to your system for the rest of your life, like poor Schopenhauer. So at that point I fell totally completely passionately endlessley eternally in love with John Keats. And mainly the information that was in his letters.

Keats was born in 1795 and died in 1821 at the age of 26. These letters were written between 1817 and 1820, so Keats is in his early 20's, 23 or 24. This first quote gives you some sense of his sense of commitment to poetry:

April 17, 1817-- I find I cannot exist without Poetry--eternal Poetry--half the day will not do--the whole of it--I began with a little, but habit has made me a Leviathan. I had become all in a Tremble from not having written anything of late--the Sonnet overleaf did me good. I slept the better las tnight for it--this Morning, however, I am nearly as bad again.

Less than a month later, he begins to really get into it--get led by the pursuit:

May 10, 1817--I've asked myself so often why I should be a poet more than other men, seeing how great a thing it is--how great things are to be gained by it--what a thing to be in the mouth of Fame--that at last the idea has grown . . . monstrously beyond my seeming power of attainment . . . Yet 'tis a disgrace to fail, even in a huge attempt; and at this moment I drive the thought from me . . . However I must think that difficulties nerve the Spirit of a man--they make our prime objects a refuge as well as a passion . . . the looking upon the Sun, the Moon, the Stars, the Earth and its contents, as materials to form greater things--that is to say, ethereal things . . .

At this point, he's climbing, in some sense, out--really climbing out of the matter universe, and there's a flicker, kind of a flicker, of a real gnostic consciousness: how we have to climb back through all the realms, all the concentric spheres of matter, like the planetary spheres, the zodiacal spheres, back into the immaterial. And one way to do that-- use it all up-- every minute. Let's go on. Here's a quote about the long poem.

October 8, 1817-- Why endeavor after a long poem? To which I should answer, do not the lovers of Poetry like to have a little Region to wander in, where they may pick and choose, and in which the images are so numerous that many are forgotten and found new in a second reading: which may be food for a week's stroll in the Summer? . . . Besides, a long poem is a test of invention, which I take to be the Polar star of Poetry, as Fancy is the Sails--and Imagination the Rudder.

| Amira Baraka and Diane di Prima |

|

I find myself very often when I'm reading something someone gives me, I find myself saying, "you sound like you're just getting started." You know, at the point where the poem finishes. Why not go on for twenty, fifty more pages? "Cause what we tend to kind of like to do is put our toe in?--or like peek in through the door and stay on the threshold. And if you go past the point where you know what you're talking about and then thru all the blather that goes after that, you might come out in an inner chamber, you know? You just might. You might blather for the rest of your life--a lot of us do--but that's a chance you gotta take. Anyway . . .

Here's a take he did on genius, a take on what "a man of genius" is:

November 22, 1817 -- Men of Genius are great as certain ethereal chemicals operating on the Mass of neutral intellet--abut they have not any individuality, any detrmined Characer--I would call the top and head of those who have a proper self Men of Power . . . I am certain of nothing but of the holiness of the Heart's affections, and the truth of Imagination.What the Imagination seizes as Beauty must be truth--whether it existed before or not,--flr I have teh same idea of all our passions as of Love: they are all, in their sublime, creative of essential Beauty . . . The Imagination may be compared to Adam's dream,--he awoke and found it truth:--I am more zealous in this affair, because I have never yet been able to perceive how anything can be known for truth by consecutive reasoning--and yet it must be. Can it be that even the greatest Philosopher ever arrived at his Goal without putting aside numerous objections? However it may be, O for a life of Sensations rather than of Thoughts! . . . I scarcely remember counting upon any Happiness--I took not for it if it be not in the present hour,--nothing startles me beyond the moment. The Setting Sun will always set me to rights, or if a Sparrow come before my Window, I take part iin its existence and pick about the gravel.

This quote, for me, has three different nuggets. First, the thing he goes back to often and later about having--here he says the man of Genius and later he says the poetic character--having no individuality. Later, he goes into it in more detail and talks about partaking in the life of every creature. Really, what he's trying to get at, or describe, seems to be some kind of egoless state. There wasn't that kind of vocabulary in England, thank God, in 1817--thank God, because otherwise he might have said: "Hey man, I just reached a far-out ego-less state the other day, watching this sparrow," and we wouldn't have what we have got.

Then Keats' idea of the imagination, which is really not that different from Blake's--the imagination creates worlds. It brings into being whatever it can vividly and completely conceive. "The imagination may be compared to Adam's dream, he awoke and found it truth." Creative imagination: that idea keeps growing with him all through his life. Somebody, a little old lady in Phoenix--it was one of those question and answer periods after a reading--asked me what I thought the function of the poet was in this society. And I said that if you could imagine anything clearly enough, and tell it precisely enough, that you could bring it about. Anyway, the theory of imagination as creative principle keeps growing for Keats. It is for him--as for Blake--a cornerstone.

And the third thing here--for me, one of the guiding sentences of twenty years of my life, or maybe still, maybe always--is, "I am cerain of nothing baut the holiness of the heart's affections and the truth of the imagination." That about says it.

Okay, this next is a paragraph that relly got Olsoon off, he quotes it a lot--it's the passage on negative capability. It's very interesting, and these things: imagination, genius as a kind of egolessness, are all part of it. There is a system here, if you wanted to sytemize it. There is a growing system of thought that Keats is evolving, but systemetizing it would be simplistic--it would do him an injustice. As Keats said, "I have never yet been able to perceive how anything can be known for truth by consecutive reasoning." I want to just take the quotes and look at them--follow him chronologically through the process.

December 22, 1817--[The winter solstice, by the way.] The excellence of evry art is its intensity, capable of making all disagreeables evaporate from their being in close relationship with Beauty and Truth . . . several things dove-tailed in my mind, and at once it struck me what quality went to form a Man of Achievement, , especialy in Literature, and which Shakespear possessed so enormously--I mean Negative Capability, that is, when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason. Coleridge, for instance, would let go by a fine isolated verisimilitude caught from the Penetralium of mystery, from being incapable of remaining content with half-knowledge. This pursued through volumes would perhaps take us no further than this, that with a great poet the sense of Beauty overcomes every other consideration, or rather obliterates all consideration.

So, at this point what Keats is calling "a sense of beauty," what obliterates all consideration or all thinking process, is that same experience that we have whenever it all drops away. A kind of satori. My friend Katagiri Roshi, who's a Zen master in Minneapolis, gave six lectures once on the word WOW. WOW, as the complete American Zen experience. When it all drops away, when the sense of beauty obliterates all consideration, or the sense of the overwhelmingness of it, WOW, that's all we said for the lat three days, me and my two friends, as we drove here from California, through all this incredible country, and we kept saying . . . they were asleep one night and I'm driving, and saying WOW! WOW!

Negative capability. Now you see how that idea, first of the man of genius not partaking of any inidividual character, becomes a bigger ormore universal idea, which is that idea of negative cpability, of not pursuing any viewpoint. It's kind of a real Eastern idea. Except that it happened fresh from nothing at this point in this kid in some dumpy English suburb. "When a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason." And to get that state, clearly enough focused to make it the matter of poetry, so taht you don't try to "make sense," but become this receiving tube, become this focusing point.

I have been asked, "how does the artist function in society?" I'm not saying that the high role of the artist is to function in society at all. But the way that your art does function socially is that when you can visualize clearly any possible human state, or social state for that matter, or universe, and focus it clearly and precisely enough, and then bring it into being either verbally in a poem, or in a painting--you bring that world into existence. And it's permanently here, it doesn't go away. Doesn't even go away when the book gets burned, look at Sappho. Those worlds don't go away.

Question: Do you see any contradiction between that and a statement by Picasso that one should have an idea of what one wants but not too precise an idea.

Oh, no! I don't see any contradiction. Because, you see, the idea of what you want, it's just your launching pad, just what you start off from, it has nothing to do with what you make. When you get through that threshold and you enter the chambeer, that's where you start to see clearly. If your idea is too precise, you might be at that door forever. You know, 'cause you might have the wrong combination for the lock. For example, I might say I know this next part of this poem has to have that feeling of line that they had in paintings in Sienna. I don't mean anything but that I have a feel of something about to happen there. That's a non-precise idea, and at that point, that's all you have. And then when you enter into the act of composing, at that point you have nothing--everything drops away, and you have only what you're receiving. Your whole purpose as an artist is to make yourself a fine enough organism to most precisely receive, and most precisely transmit. And at that point--total attentiion to total detail, total suspension of everything but that vision, whatever it is, and gain, at that point, no idea at all, no idea. The idea was just your first--the idea is what made you get up that morning and put your shoes on. And when you find yourself in an incredible grove, it's not because you had an idea you were gonna get there. But when you get to the grove, you damn well better open your eyes. It's two different parts of the process. More Keats . . .

February 3, 1818. Poetry should be great and unobtrusive, a thing which enters into one's soul and does nt startle it or amaze it with itself--but with its subject . . . we need not be teased with grandeur and merit: when we can have them uncontaminated and unobtrusive.

|

| Poet Diane di Prima |

Note: more text of Diane di Prima's lecture

on Keats/Light and his notion of

"negative capability"

to be uploaded by maryclaire

this weekend . . .

I will do my best, it's a lot of typing.

March 7, 2003

"The Struggle"

an excerpt from her book Between Lives by

Dorothea Tanning

'Thus I have come one morning to the studio, into the litter and debris of last week and the day before. Tables hold fast under their load of tubes and brushes, cans and bottles interspersed with hair roller pins, that view of Delft, a stapler, a plastic tub of gypsum powder, a Polaroid of two dogs, green flashbulbs for eyes, a postcard picturing the retreating backs of six nudists on a eucalyptus-shaded path, a nibless pen, an episcope (an optical projector). On the floor or on the wall or on the easel, a new surface waits whitely.

Dorothea Tanning

Battle green, blood geranium, rubbed bloody black, drop of old rain. The canvas lies under my liquid hand. Explosia, a new planet invented with its name. That's what we paint for, invention. Unheard-of news, flowers, or flesh. "Not a procedure," I say to the room. "Nothing to do with twenty-four hours: just an admixture for all five senses, the sixth one to be dealt with separately."

Because this is only the beginning. A long flashed life, as they say, before dying. I am a fish swimming upstream. At the very top I deposit my pictures; then I die as they ripen and hatch and swim down, very playfully, because they are young and full of big ideas. Down and down, and finally, among the people who like to fish pictures, they are caught and devoured by millions of eyes.

In this artist's dream-plot there are only artist-scales, iridescent though they may be. And the rest? For thirty-five years, life was love, a second skin. Authoritative, instinctual love. Now life is life, sybaritic, an absolutely polished structure of skeletal simplicity. Uninvolved, uncommitted, underworn, deeply and evenly breathed. Its second plot, not life but art, unfolds painty wings each day to try the air, pushing out perhaps reluctant visions, uninvolved, yes, unaware of their public category.

It is one of those days and it is time to reconsider. Time to turn inside out before the first gesture. You have drawn up a stool and sit gazing at the first whiteness, feeling suddenly vulnerable and panic-stricken before your light-hearted intention. What has happened, where is the euphoria, the confidence of five minutes ago? Why is certainty receding like distance, eluding you, paling out to leave the whiteness as no more than a pitiless color? Is a canvass defiant, sullen? Something must be done.

Ambivalent feelings, then, for the blank rectangle. On one hand the innocent space, possibilities at your mercy, a conspiracy shaping up. You and the canvass are in this together. Or are you? For, seen the other way, there is something queerly hostile, a void as full of resistance as the trackless sky, as mocking as heat lightning. If it invites to conspiracy it also coldly challenges to battle.

Quite mechanically during these first moments - hours? - the little bowl has been filled with things like turpentine and varnish; tubes of colour have been chosen, Like jewels on a tray, and squeezed, snaky blobs, onto a paper palette. The beautiful colors give heart. Soon they will explode. A shaft of cobalt violet. With echoes from alizarin and titanium and purple - which is really red. There is orange from Mars, mars orange. The sound of their names, like planets: cerulean and earthshadow, raw or burnt; ultramarine out of the sea, barite and monacal and vermillion. Siren sounds of cochineal and dragon's blood, and gamboge and the lake from blackthorn berries that draw you after them; they sing in your ear, promising that merely to dip a brush in their suavities will produce a miracle.

What does it matter that more often not the artist is dashed against the rocks and the miracle recedes, a dim phosphorescence? Something has remained: the picture that has taken possession of the cloth, the board, the wall. No longer a blind surface, it is an event, it will mark a day in a chaotic world and will become order. Calm in its commotion, clear in its purpose, voluptuous in its space.

Here it is, seduction taking the place of awe. After a quick decision - was it not planned in the middle of the night along with your subject and its thrust? - a thin brush is chosen, is dipped and dipped again - madder, violet, gold ocher. A last stare at the grim whiteness before taking the plunge, made at last with the abandon "of divers," said Henry James, speaking of birds, "not expecting to rise again." Now, after only seconds, blankness and nothingness are routed forever.

A hundred forms loom in charming mock dimensions to lure you from your subject, the one that demands to be painted; with each stroke (now there are five brushes in two hands) a thousand other pictures solicit permanence. Somewhere the buzzer buzzes faintly. Sounds from the street drift up, the drone of a plane drifts down. The phone may have rung. A lunchless lunch hour came and went.

The beleaguered canvass is on the floor. Colors are merging. Cobalt and chrome bridge a gap with their knowing nuances. Where is the cadmium red-orange? The tubes are in disorder, their caps lost, their labels smeared with wrong colours.

Oh, where is the red-orange, for it is at the moment the only color in the world and Dionysus the only deity.

Now there is no light at all in the studio. The day is packing up, but who cares? With a voice of its own the canvass hums a tune for the twilight hour, half heard, half seen. Outlines dance; sonic eyes bid you watch out for surprises that break all the rules: white on black making blue; space that deepens with clutter; best of all, the fierce, ambivalent human contour that catches sound and sight and makes me a slave. Ah, now the world will not be exactly as it was this morning! Intention has taken over and here in this room leans a picture that is at last in league with its painter, hostilities forgotten. For today.

As brushes are cleaned and windows opened to clear the turpentine air, the artist steals glances - do not look too long - at the living, breathing picture, for it is already a picture. Once again light-hearted, even light-headed, the mood is vaporous. There are blessed long hours before tomorrow...

Have I slept? Once again before the daubed canvas, which is now upright in the harsh morning light. I am aghast. How could anyone have found it good, even a good start.? Traitorous twilight, fostering those balloons of pride that had floated all over the studio! Yesterday ended in a festival, was positively buoyant. Syncopating with glances canvasward, brush-cleaning drudgery was a breeze (a hellish task after a failed day). Now you are bound. The canvas is to be reckoned with. It breathes, however feebly. It whispers a satanic suggestion for the fast, easy solution. "Others have done it, do it, why not you?" How to explain? There is no fast and easy for me.

Daily depths of depression, as familiar as a limp is to the war-wounded, are followed by momentary exhaltations, sometimes quiet certainties: Yeah, that's it... But if that is it, then the presence... on... the other side... all changed now, dark again... Must wait for tomorrow... Oh God... How awful...

Several days have left their gestural arabesques in the big room, adding up to clutter and despondency. Dust has been raised in the lens of the eye; intention has softened to vagary. Then an idea in the night brings its baggage to the morning. Welcome! Go ahead. Stare at the canvass already occupied by wrong paint, hangdog. But not for long. Not this time. Because you dive - with an intake of breath you dive, deep into your forest, your desert, your dream.

Now the doors are all open, the air is mother-of-pearl, and you know the way to tame a tiger. It will not elude you today, for you have grabbed a brush, you have dipped it almost at random, so high is you rage, into the amalgam of color, formless on a docile palette.

As you drag lines like ropes across one brink of reality after another, annihilating the world you made yesterday and hated today, a new world heaves into sight. Again the event progresses, without benefit of hours.

Before the emerging picture there is no longer panic to shake heart and hand, only a buzzing in your ears to mark rather unconvincingly the passage of time. You sit or stand, numb in either case, or step backward, bumping as often or not into forgotten objects dropped on the floor. You coax the picture out of its cage along with personae, essences, its fatidic suggestion, its insolence. Friend or enemy? Tinged with reference - alas, as outmoded these days as your easel - weighted as the drop of rain that slid on the window, it swims toward completion. Evening soaks in unnoticed until lengthening shadows have caressed every surface in the room, every hair on your head, and every shape in your painted picture.

The application of color to a support, something to talk about when it's all over, now hold you in thrall. The act is your accomplice. So are the tools, beakers, bottles, knives, glues, solubles, insolubles, tubes, plasters, cans; there is no end...

Time to sit down. Time to clean the brushes, now become a kindly interlude. Time to gaze and gaze; you can't get enough of it because you are now on the outside looking in. You are merely the visitor, grandly invited: "Step in."

"Oh, I accept." Even though the twilight has faded to black and blur, making sooty phantoms of your new companions, you accept. Feeling rather than seeing, you share exuberance. You are surprised and uneasy when you seem to hear the rather conspiratorial reminder that it was, after all, your hand, your will, your turmoil that has produced it all, this brand new event in a very old world. Thus, you may think:" "Have I brought a little order out of the chaos? Or have I merely added to the general confusion? Either way a mutation has taken place. You have not painted in a vacuum. You have been bold, working for change. To overturn values. The whirling thought: change the world. It directs the artist's daily act. Yes, modesty forbids saying it. But say it secretly. You risk nothing.'

--Excerpt from 'Between Lives'

by Dorothea Tanning, 2001, Norton.

In 1975, Tanning spent eleven months trying to cope with the stroke-smitten, powerless, angrily powerful Max Ernst. Her husband and soul-mate of so many years and so many homes survived a head wound in the Great War, survived the Nazi invasion of France, escaping Paris, then Marseilles by the skin of his teeth and in 1942 met the much younger Dorothea, a struggling illustrator, at her New York apartment. Seeing her painting, 'Birthday', seeing that she played chess, seeing her... he never left.

"The Struggle" was written in her solitary state, returned to New York, refinding her own voice without her Max's dominating fame and presence. All her contemporaries were gone: the Belgian and Parisian Surrealists, free-spirited American women: Kay Sage, Lee Miller, great friends, John Cage, Marcel and Teeny Duchamp, Merce Cunningham, George Balanchine, Julien Levy, Dylan Thomas, Truman Capote... She continues to work at the age of 92.

below: "Birthday" by Dorothea Tanning, 1942

'Surrealism: Desire Unbound' at the Tate Modern

A Review by Borin Van Loon

Not a 'blockbuster' exhibition, if such a thing exists, and probably all the better for it. As one of the most important, turbulent and, it must be admitted, inherently flawed movements in art, poetry and revolutionary politics of the last century, Surrealism explores and uncovers that which is 'above the real', a dimension of meaning which transcends bourgeois 'common sense'. Given their positioning in history (born out of the unbridled nihilism of Dada, itself a product of the horrors of the Great War) the founding fathers of Surrealism (and it was mainly men at the start: women were seen as muses for the males) didn't have much time for that dominant and dreaded class dubbed by Marx 'the bourgeoisie'. Uneasy off-and-on relations with the official Communist Party throughout the Stalinist era didn't really help; it's clear that the hard left in France couldn't cope with these semi-anarchic, strange young men and their passionate, disturbing attitudes towards the stifling mediocrity of the European middle class.

At the centre of Surrealism's agenda was the pursuit and examination of desire. The word 'desire', as it appears in the title of this exhibition, applies to all areas of human activity which are suppressed by bourgeois values. Adopting the spirit and vocabulary of the Russian Revolution and Freudian psychoanalysis (two unlikely bedfellows) led the early practitioners to experiment with pure psycic automatism, often to the exclusion of other forms of expression. These factors conspired to destabilise a movement which was remarkably long-lived, eventually being shattered only by the invasion of France by the Nazis. As a coherent movement Surrealism found a figurehead (and he did have a remarkably large, leonine head) in Andre Breton. Breton himself embodied a revolutionary spirit with a questionable attitude towards women and extreme homophobia. During the 'Discussions on Sexuality' which were transcribed in the thirties and published in full only recently, Breton threatened to terminate discussions which wandered into same-sex practices on several occasions. Given the free-ranging and openly frank intentions of these group discussions, his impulses mark him out against many of the more liberal participants. Needless to say, any women present remained largely silent or were busy acting as secretary.

Many of the prejudices and contradictions inherent in society as a whole were embodied by the Surrealists. Successive expulsions from the group were often followed by tacit reacceptance into the fold, in typical French counter-cultural mode (see also: Situationists whose leader Guy Debord eventually expelled everyone from the inner core except himself). The group were destined to drag their remnants back together after the war and find Breton at the centre of a new generation of followers in Paris, though with diminished influence. Jean-Paul Sartre had a very existential and jaundiced view of Surrealism, but I wonder what Simone de Beauvoir would have had to say about the bundle of Maoist contradictions which was Sartre.

Slavish adherence to automatism, even though it had contributed notable work such as the prose-poem 'Magnetic Fields' by Breton and Paul Eluard and the automatic drawings and paintings of Andre Masson, led to freer expressions. Salvador Dali, whose extreme posturing shocked even the Surrealists, invented the Paranoic-Critical Method of capturing dreams and nightmares on minutely detailed canvasses. The dazzling vision and technique of these paintings from the thirties, as well as his 'symbolically-functioning objects' and poems comprise major works of the movement.

The Tate Modern offers us all the usual suspects from its own collections and many rarities from around the world. Magritte is here only sparingly ('The Lovers' 1928), some major Ernsts ('The Robing of the Bride' 1940), fine sculptures by Giacometti ('Woman With Her Throat Cut' 1932, shown left) , great photography by Man Ray and Lee Miller ('Anatomies' 1929), and good selections from the man-child paintings of Miro. Meret Oppenheims 'Object', which set American society alight when it was first shown at the Museum of Modern Art, demonstrates the characteristic paradox of object and material: a cup and saucer covered in fur. Man Ray's flat-iron which has a row of nails welded down the centre of its pressing surface, 'Gift', embodies the same feeling of unease: an object which destroys that which it is intended to improve. On the ironing theme, Marcel Duchamp proposed his own version of the surrealist object: the Old Master painting which is used as an ironing board.

An extensive selection of documents, photographs and letters lies at the heart of this exhibition. Not spectacular in itself, this gallery contains much of the restless spirit of Surrealism. The star of the show for me was the painting 'Gradiva' by Andre Masson (shown above). Based on its own borrowed myths and references it contains - quite literally - volcanic sexuality and a part human, part stonework female figure bisected by a joint of meat (shades of Stanley Spencer here), with a conch shell instead of genitalia.

In the words of the Comte de Lautremont: it's as beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of an umbrella and a sewing machine. At its best, it quite takes the breath away. We all know that Surrealism continues to be the currency of much of today's advertising. One only has to look at some of the slightly repellant television advertisments on our screens (BBC internet: walking fingers with little human heads; a monstrous computer-generated baby which rampages through a hospital like Ridley Scott's alien: some make of car or other) to see its dominance. Meanwhile it reverberates in the stand-up comedy of Eddie Izzard and Emo Philips and the film-making of David Lynch, David Cronenberg and Jan Svankmajer. It informs comic strips (modesty forbids...) and situation comedy ('Fast Show', 'Big Train', 'Smack the Pony'). "It's quite surreal" has become a commonplace amongst people who have no idea what surrealism is; quite often the situation so described isn't really surreal at all (see also 'Kafkaesque').

Finally, one of my favourite artists, Dorothea Tanning, soul-mate of Max Ernst and a superb painter to boot, leaves me with the most memorable of images. 'Birthday' (1942, shown left) is a full length selfportrait of the artist at the age of thirty, bare breasted and standing in front of an endless succession of open doors. At her feet a grotesque succubus crawls. In the specialist shop afterwards I spend 45 minutes and loadsamoney on my choices. Tanning's autobiography, a book of automatic texts (including 'Les Champs Magnetique') and Michel Foucault on that most equivocal Magritte work: 'Ceci n'est pas une Pipe'. A crystal paperweight with the enlarged eye of Lee Miller at its heart and a few postcards and I am done. Disappointingly no t-shirts (I didn't really want one of the extortionate 'TATE' ones with the lettering composed of three dimensional Dalinian ants). But, all in all, an exhilarating show.

As I walk into the huge halls of the Tate's main exhibition area, I'm drawn by a crowd huddled into one of the mini-cinema areas where once the full-frontal film of a naked artist disporting himself was shown. There, transfixed, visitors stare at the projected animations of Jan Svankmajer. 'Dimensions of Dialogue' explores two clay-sculpted heads on a table top as they stare with glass eyes at each other in an unnerving manner and fence with a variety of objects which issue from their mouths. One of the finest pieces of film making in the history of cinema.

--Borin Van Loon, January 2002

The Surrealism exhibition ran from 20 September 2001 to 1 January 2002 at the Tate Modern in London. Our Chairman Borin Van Loon went along and sent us this review.

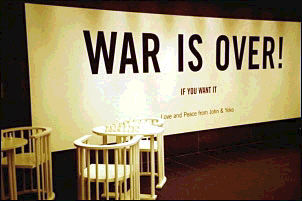

Yoko Ono: Yes

Retrospective, 2001

MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge

Many people know Yoko Ono only as John Lennon's widow, the woman who staged high-profile protests with the former Beatle during the height of the Vietnam War, and later witnessed his murder at the hands of a deranged fan.

Detractors condemned her as the dragon lady responsible for the Beatles' breakup and a social climber who garnered publicity on the back of her world-famous husband.

But few know Ono the artist, who left Japan with her parents to settle in New York, and later played a vital role in the artistic avant-garde. The survey of her work from the 1960s to the present currently on display at MIT List Visual Arts Center may change all of that.

From the start of her career, Ono was on the front lines with New York's most accomplished creative minds.

She aligned herself with Fluxus, a late 1950s-early '60s group of artists in southern Manhattan who sought to erase the boundaries between music, poetry, visual art and performance. Trained as a classical pianist, Ono's association with the group brought her in contact with multidisciplinary artists, such as underground composer La Monte Young and video artist Nam June Paik, who also began his career as a composer.

Many of Ono's seminal pieces are in the List Center's survey of her work. These include her "instructions paintings" texts that suggest actions the viewer should take, or ideas that one could visualize and sculptures, films, drawings, as well as posters, photographs and videos that document "happenings" and "events" that she staged through her career.

Short films that she made, including "Fly," which features close-ups of a house fly walking on the recumbent body of a nude woman, and "Cut Piece," which documents a performance in which Ono sat motionless on a stage and invited audience members to cut her clothing away, are given continuous screenings in the exhibit.

Greeting visitors to the List Center is "Sky TV," a TV monitor displaying a closed-circuit live video feed of the sky above the gallery. The piece is typical Ono, circa 1966 groundbreaking, as video art was in the mid-1960s, seeking out beauty in the frequently overlooked fabric of everyday life, and presenting that beauty in an unexpected context.

Much of Ono's work has been defined as conceptual in nature, that is art made with an emphasis on the idea behind the work and a deliberate effort to de-emphasize craftsmanship. In most instances, Ono commissions others to fabricate her art objects an act that puts the artist at a physical distance from her work and divides her artistic decision making and the hand labor that goes into making it into two distinct categories.

"Yes," the piece from which the exhibition takes its name, was the work that she exhibited at her now famous 1966 exhibition at the Indica Gallery in London. The piece consisted of a white stepladder that viewers were invited to climb. Hanging on a chain from the ceiling was a magnifying glass. Viewers could use the magnifying glass to read a tiny piece of text on the ceiling. The text merely read "Yes."

As Beatles aficionados may recall, it was at that exhibition she met John Lennon. Lennon said in later interviews that he felt relieved that "Yes"'s message revealed something affirmative, as opposed to what he thought was the negativism of the avant-garde in that era. Lennon and Ono married in 1969.

The List Center is exhibiting the ladder that was used in the 1966 exhibit.

But if you're hoping to climb the same rungs that Lennon once scaled, you're in for a disappointment. The ladder, and the platform on which it rests, are off limits to visitors. Not for safety reasons, as one might assume, but because the ladder must be kept in archival condition understandable, yet that changes the piece markedly. Ono's work blurs the distinction between artist and spectator, allowing the spectator to complete the piece through an activity." In its current installation, "Yes"'s true message is only hearsay.

Had non-historic objects been used in place of the original ones, "Yes" may have sacrificed some of its nostalgic kick but paradoxically gained a great deal in authenticity.

This is a small complaint, however. The outstanding quality of works presented, and the breadth of Ono's artistic achievement offers much to consider and debate. Her reputation will undoubtedly be bolstered wherever this exhibition travels. Paul Parcellin

|

|

Bringing La Bohème to Broadway

Part I - Becoming Part of the Cast

My journey with the "Broadway Bohème," as it has come to be called by cast and crew, began in autumn of 2000. I was in my last year of graduate school as a voice major at Boston University. I saw an ad on a music department bulletin board that said something like, "Baz Luhrmann, Director of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet and Strictly Ballroom, is casting for a production of La Bohème, to be mounted on Broadway."

The ad caught my eye, but I was skeptical. I love Strictly Ballroom, a great movie, but La Bohème on Broadway? Would they perform the actual Puccini score, or would it, like the show Rent, be a new score loosely based on the same story, but having nothing at all to do with "opera" singing? Would the show be in Italian, like the opera? I blew off the ad. I thought it was an interesting idea, but would never get off the ground, so I forgot about it.

Fast forward to ten months later. I graduated with my Master's degree and moved to New York City. I was lucky enough to be signed with a manager right away, Martha Wade, who mentioned to me that the "Broadway Bohème" was still not cast, and that she could get me an audition. Several things piqued my interest. First of all, I discovered that this Bohème would indeed be the Puccini score, and that it would be in Italian. Also, since I had first seen the ad, the movie Moulin Rouge, directed by Baz Luhrmann, had been released. I thought it was incredible.

I went to my first audition full of trepidation. What on earth would these people be looking for? The other singers in the waiting room definitely did not look like the people I usually see at opera auditions. Opera singers, unlike actors, usually dress pretty conservatively, and aren't well, um... hip. Clearly the singers had seen Moulin Rouge and were trying to look as colorful as possible to impress Mr. Luhrmann! I guess I had the same motive, but I went about it in a different way. Instead of the simple but slightly sophisticated red dress I usually wear to auditions to make me look older and more experienced, I wore a little black dress that I wear to go out for cocktails with my friends. (Opera audiences, generally focusing on the voices rather than the acting, will accept singers who are much older than the characters they are playing, or even one who weighs in at 300 lbs. playing a pretty young thing, but Broadway audiences are much more visually oriented. I figured it couldn't hurt to show off the fact that I am young - about the same age as the bohemians in La Bohème!)

This first round of auditions (the first of many, but we'll get to that later) was judged by two women from the casting agency. I decided to sing the aria Quando m'en vo from Puccini's opera. I was in really good voice and gave what I thought was a persuasive dramatic interpretation, but once I finished, the women on the panel wanted to hear it again. This time they gave me some directions - "make eye contact with us, use the whole room," etc. I sang the whole aria again, and I heard the very next day that I had been called back!

Over the next ten months I was called back eight times! I sang for the producers. I sang for the musical director. I sang for Baz, but it seemed there was always another round to make it through. In February, 2002, I was in Tampa, Florida under contract to sing with the opera there. Word came that Baz was about to make his final selection, but I would have to be in New York City for just one more audition! Groan! After much negotiating, begging and pleading, the conductor agreed to release me from one day of rehearsal in Tampa so I could fly back to NYC. This meant waking up at 4 am, getting on a plane at 6:30 am, and singing for Baz at noon. This would be tough!

At my audition, Baz and his assistant followed me around with a hand-held video camera, sometimes putting it right up in my face while I was singing. In all my training no one had ever prepared me for anything like this audition! I also had my picture taken in all sorts of poses. "What was THAT??!!" I thought as I ran to catch my flight back to Tampa, where a message was waiting for me: I was in the original cast of La Bohème!

I have heard varying reports of how many singers were auditioned for this La Bohème, anywhere from 3,000 to 20,000 from all over the world. It took over two years to assemble a cast of 50, which includes some singers who don't speak a word of English.

Part II - From Costume Fittings to California

|

After hearing I would be a member of the original cast of Baz Luhrmann's La Bohème on Broadway, things seemed to start happening at lightning speed. The contract came in the mail, and I learned that the rehearsals would be occurring in San Francisco, California. We would also be doing six weeks of shows in San Francisco at the Curran Theatre, before moving to Broadway in November. Baz said he would attend every single performance in California (8 per week!) to make sure Bohème would be everything he dreamed it could be, before moving it to NYC where it will be scrutinized by critics from all around the world.

While in New York, I was instructed to go to a wig fitting at a loft apartment in an unfamiliar neighborhood in downtown Manhattan. It was rainy, cold, and miserable, and I got lost trying to find the address. When I rang the buzzer, I was not in the best mood. What happened next was like magic. The door opened, and inside this unassuming and unmarked building was an enormous and blindingly colorful world of artists, designers, and craftsmen, all busily running around with sketches, model sets, and fabrics. The woman who answered the door was none other than Catherine Martin - Baz's wife and creative partner, and Academy Award winner for her costume designs in Baz's movie Moulin Rouge. Although I had never met her before, she greeted me by name. "Baz would love to say hello as well, but CBS is here interviewing him," she said.

I saw that there were pictures on the wall of all the cast members with sketches of costumes taped beside them. There were beautiful and intricate models of the sets for Bohème, and what seemed like a hundred people gathered around Catherine, or bent over desks with colored pencils. I saw Baz giving a tour to the news crew from CBS. He was speaking so excitedly about the work being done, and explaining to the crew that he and Catherine live in the back of the design studio. It was in their bedroom that I had my wig fitting! Two Italian men who also did the wigs for Moulin Rouge, Romeo and Juliet, and Strictly Ballroom put a wig cap on me and traced the outline of my natural hair. This is so when the wig is made, it will match my real hairline so precisely that the audience won't be able to tell I'm not using my own hair.

On a later date I had a costume fitting with Catherine Martin and her incredible team. Catherine and Baz are Australian, as are most of their assistants. Five good-natured Australians pulled and pinned my costume until it met Catherine's approval. All costumes in Bohème were made from scratch to the exact measurements of the cast.

In the next few weeks I made plans to move to San Francisco for nine weeks - three weeks of rehearsal, and six weeks of performances. As I prepared to leave New York, the buzz about Bohème began to be palpable. There were articles in Time Out magazine and The New York Times, and the full-page color ads and commercials began to run daily. It dawned on me just how enormous and ambitious this project really is, and that's when the nerves set in!

The entire cast traveled together on September 8th. We met in front of the Broadway Theatre at 53rd street (where we will be performing), took chartered buses to JFK Airport, and flew on a Continental jet to San Francisco. I couldn't believe how friendly the other people were, and how darn good looking!

Once in California, we settled into our different residences and prepared to start rehearsals first thing the very next morning.

|

Part III - Rehearsing with Baz Luhrmann

|

|

The day after the cast of the Broadway Bohème descended on San Francisco, we all boarded vans and were taken to a section of town called the Presidio, where we would be rehearsing for the next two weeks in the shadow of the Golden Gate Bridge. (Most Broadway-bound shows have their out-of-town trial runs in Peoria; how nice it is that ours is in San Francisco, one of America's great cities!)

That first day was a very exciting one, with so many new people to meet,

|

and a dramatic presentation by director Baz Luhrmann and his wife Catherine Martin about their vision for the project. Baz and Catherine are the brains and heart behind this Broadway Bohème. We got a sneak preview of the promotional ads that would be running on television, took a virtual tour of the stage sets still under construction, and marveled at the sketches of Catherine's gorgeous costumes.

Baz's plan is a simple but courageous one. He wants to bring opera back to the masses (Wasn't Giacomo Puccini the Stephen Sondheim of the Nineteenth Century, and even more popular, at least in Europe, than his 20th-Century colleague?), but not by watering it down. This Bohème is completely intact musically, just as Puccini wrote it, and will be performed in Italian. Baz says he wants to bring back the excitement and feeling of spontaneity that traditional opera often lacks. He wants every moment to be believable. What a concept!

Rehearsals were run with this idea in mind. All of us were given direction from Baz, but were encouraged to fill in the details of the lives of our characters with our own creative visions. We imagined what a street on Christmas Eve in Paris in 1957 would look and feel like, and we made it a reality. We spent days and days on what seemed like the smallest of adjustments, put those changes into our Parisian street, and the results were magical. A detailed and individual journey exists for every single person onstage, not just the principal characters as is almost always the case in opera.

After a couple of weeks in our temporary rehearsal space in the Presidio, we moved into the Curran Theatre just off Union Square. At the first viewing of the stage set, the cast was speechless. It is a breathtaking work of art. The setting itself, predictably, was applauded by our audience every night. But once we started rehearsing on it, we felt like we were starting our staging all over again. Nothing happened the way we had rehearsed it, and people were running into each other and tripping over platforms and other pieces of the scenery. It took another week to work out the kinks and get the show running smoothly. How quickly that week in the theater raced by! And how the enthusiasm was growing in all of us!

Now it was time for the first invited audience to savor the show. We had two weeks of previews in San Francisco. (Previews are presented prior to the official Press Opening. No reviews can be written at these performances.) I was very nervous. Would they love it? Would they boo us off the stage? The preview audiences, I am pleased to report, loved the production! Every time the curtain fell we got cheers and standing ovations. However, even with the adulation of the audience, the two weeks of previews were very stressful. Baz was still changing details of staging right up to moments before we went onstage. We tried new things every night in front of a live audience, and continued to make changes until Opening Night.

Opening Night in San Francisco was a star-studded affair, with many celebrities in attendance. From the stage I spotted Nicole Kidman, Kevin Spacey, Andy Garcia and George Lucas. The cast tried to go about its predetermined stage business, but we were all secretly trying to get glimpses of the stars in the audience. After the performance the entire cast was invited to a bash at the famous Ruby Skye nightclub. The celebrities were all there congratulating Baz, Catherine and the singers. It was an extravagant feast with mountains of food. All of us danced until the sun came up!

There was still one more test: what would the San Francisco critics say? I dashed to the store the next morning to pick up the local newspapers, which I shredded in my exuberance to find the critiques. Aha! The headlines said it all: "Simply Sensational - Luhrmann's Broadway-style 'Boheme' sets a new standard for musical theater," according to the Chronicle, and The Examiner said "Brilliant Bohème - Baz Luhrmann's take on the Puccini classic, at the Curran Theatre, perfectly balances tradition and innovation."

That we were really a hit was apparent as I walked past the theater later that afternoon and observed the box office line wrapped all the way around the block! Within days every ticket to the six-week run in San Francisco was gone. Friends from high school and college called me desparately in need of tickets, but there was nothing I could do. There wasn't a single ticket available.

On the date this article was written, there were two more weeks of performances in San Francisco still to go. On November 11th the cast flies back to New York City for a week of rest before beginning another sequence of rehearsals with Baz in the Broadway Theatre at Broadway and 53rd Street.

Will this spectacular and moving operatic production be a success on the Great White Way? If so, history will be made and the risk will have been worth taking. There have been other operas on Broadway, but nothing like Baz Luhrmann's production of Puccini's La Bohème.

Part IV - Back in New York

|

|

On November 11th, the very next day after our last performance in San Francisco, the cast of Baz Luhrmann's La Bohème boarded buses at 6:00 am, drove to the airport, and flew home to New York City. We had spent nine weeks in San Francisco rehearsing and performing La Bohème eight times a week to critical acclaim. The cast and crew had worked incredibly hard on the show under Baz's direction. We were rewarded with six weeks of sold-out performances and reviews so good they could have been written by Baz's mother. I felt so proud to be a part of the show. I was also completely exhausted!

While I enjoyed being on the West Coast, I was definitely ready to get back to my own apartment in New York, and very much looking forward to our week off. The week flew by in a blur of unpacking and catching up with friends, and before I knew it, I was walking into the Ford Center at 43rd and Broadway where La Bohème was rehearsing. Even though the week off passed quickly, I felt as though I hadn't seen my friends in the cast for months. We became so close in San Francisco that we are now one big family. It is amazing to me that any group of performers can get along so beautifully, but we truly do. It is a very special group of people onstage at The Broadway Theatre every night!

Rehearsals at the Ford Center lasted for only one week. There was still work being done on the sets and lights at our real home, the Broadway Theatre, at 53rd and Broadway, that made it impossible to conduct rehearsals on the actual stage. Our rehearsals were spent on intensive detail work. I was impressed with the new ideas Baz had formed since we had last seen him. He refined, cut, polished and obsessed over every moment onstage. I am continually amazed at how many things he has running around in his head at any given moment, and how he can keep them all straight.

There were many new challenges in New York. The Broadway Theatre is much larger than the Curran Theatre in San Francisco. Baz insists on only "true life" onstage, meaning no excess gesturing or "indicating." We worked hard for many days to figure out how to play to a much larger audience without losing the intimacy and the reality. Another challenge was that we have a new set of kids in the cast. The children in San Francisco were all local kids, so we started from scratch staging the New York kids into the opera.

After a week at the Ford Center, we moved into the Broadway Theatre to rehearse on the set. We had less than a week to rehearse before the first preview performance on November 29th.

Although we were received far better than our wildest dreams in San Francisco, New York audiences are much tougher. I felt excited because it was my first performance on Broadway, but very nervous about the audience reaction. At all of the preview performances, Baz talks to the audience from the stage before the start of the opera. Before he even started talking, the audience went crazy - screaming his name, cheering, and applauding. Backstage we looked at one another with huge smiles on our faces. Clearly this audience would be open to Baz's big risk - opera on Broadway.

The audience responded enthusiastically all night and gave us a raucous standing ovation at the conclusion. We got the same positive reaction at all of the preview performances. Does this mean we will be a hit?

The official opening night is December 3rd. Until then we are still called to rehearsals even if we have a performance on that day.

|

|

Part V - Opening Night in New York

|

|

Baz Luhrmann's production of La Bohème on Broadway officially opened on December 8th. The show had already been in previews for two weeks at the Broadway Theatre on 53rd Street. The audiences during previews seemed to love the show. We received standing ovations at every preview, but no one can predict how the New York critics will respond, so the cast was on pins and needles. |

Ben Davis as Marcello and Chlöe Wright as Musetta

in Act II of Baz Luhrmanns production of Puccinis La Bohème.

Photo by Sue Adler. Image courtesy Boneau/Bryan-Brown.

On December 8th, the Broadway Theatre could easily have been mistaken for a ritzy Hollywood award show. There was a red carpet surrounded by paparazzi with flashbulbs going off right and left. The list of celebrities in attendance was incredible - Leonardo Di Caprio, Sandra Bullock, Hugh Grant, Cameron Diaz, James Gandolfini, Katie Couric, and Regis Philbin, just to name a few. Baz was there with his wife and artistic partner, Catherine Martin, who looked incredible!

The first two acts of the show, which are performed with just a short pause in between, went beautifully, so the cast was already feeling pretty good, but nothing could have prepared us for the news we received at intermission. Ben Brantley, theater critic for the New York Times, had seen La Bohème during previews and written a rave review which would be in the paper the next day!

After the show, the producers threw a huge bash for the cast, audience and invited guests at the luxurious Hudson Hotel on 58th Street. It was a beautiful party, but so crowded that it was hard to find any other cast members. There were news crews circling the party, trying to get quotes from the celebrities. I went home very late, but woke up early to read the New York Times review.

In the New York Times, Mr. Brantley wrote, "Baz Luhrmann's rapturous reimagining of Puccini's opera of love in a garret turns out to be the coolest and warmest show in town, and enchanted mixture of self-conscious artistry and emotional richness......Opera critics should know that this production is no slice of wise-guy revisionism. What Mr. Luhrmann and his extraordinary production designer, Catherine Martin, have done is find the visual equivalent for the sensual beauty and vigor of the score."

The day that Ben Brantley's review appeared in the paper, La Bohème did one million dollars in ticket sales. Later in the week, that number would grow to four million.

One of the really fun perks that comes with being in La Bohème is seeing and sometimes meeting celebrities who come to see the show. Since Opening Night, the list of stars in attendance has included Michelle Pfeiffer, David E. Kelley, Steven Spielberg, Bruce Springsteen, Drew Barrymore, Bette Midler, Sarah Jessica Parker, Matthew Broderick, and former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani.

La Bohème is currently taking ticket orders through June 2003. The next big event to look forward to is the Tony Awards. We are hoping to be nominated in many different categories and hoping to perform in the ceremony which occurs every year during the first week of June.

Part VI - Behind the Scenes

|

|

Never in my wildest dreams did I imagine how hard it would be to perform the same show eight times a week for an entire year. Although La Bohème is an exciting and fun show, sometimes it is difficult to find enthusiasm in performing the same action and music over and over.

My pre-show activities are always the same. I am required to sign in at the theater at one half hour before the curtain time, at the latest. After I sign in, I walk upstairs to the ladies' dressing room, where I have a portion of the room reserved for me. My costume is waiting there for me, courtesy of the Wardrobe Department. On the way upstairs I pick up my microphone, which is tiny and on a long cord attached to a small transmitter. The transmitter goes in a special pocket hidden inside my costume, and the microphone will get hidden in my wig by the Hair and Makeup Department. In La Bohème we do our own makeup. We were given the makeup and instructed on how to apply it. Doing my makeup usually takes about twenty or thirty minutes. I am not in the first act, so my hair appointment is at the "places" call, which means at eight o'clock pm for an evening show, or two pm for a matinee. I go to the hair and makeup room wearing a bathrobe and have my wig pinned to my head. After that I go back to the dressing room, put on my costume, and wait for the stage managers to call the ensemble to the stage. When I hear the stage managers call "places" over the backstage loudspeaker, I go downstairs to the stage.

|

Jessica Comeau as Musetta with the Company

in Act II of Baz Luhrmanns production of Puccinis La Bohème.

Photo by Sue Adler. Image courtesy Boneau/Bryan-Brown.

When the show is over, I give my microphone back to the Sound Department, have my wig taken off, and take off my own costume and makeup. As I exit the stage door, there is usually a big crowd waiting to get autographs from the stars of the show.

If I am running late getting to the theater, I have to call the stage managers and tell them the situation. The stage managers have to keep track of the cast, because if somebody is absent, they must have a cover or "swing" go onstage instead. A "swing" is a person who knows many different roles in the show, who may have to step in at a moment's notice. The stage managers understand, and take into account that sometimes people are unavoidably late, through no fault of their own. However, a cast member who is consistently late runs the risk of getting fired.

Flu season in New York has caused many cast members to miss performances. There has barely been a single performance since December with the entire original cast present. Members of the ensemble accrue one sick day for every month of work. If we miss more than one performance a month, we have one-eighth of our weekly pay deducted from our paycheck. I was sick and unable to come to work on a Wednesday, which means I used two sick days because we have two performances on Wednesdays.

As an ensemble member, I cannot take a vacation for the first six months. After six months we each can take a week off, but it is on a first-come, first-served basis for requesting time off, as only one woman and one man can be away at the same time. If I don't take my vacation week, at the end of my contract in September, I will get an extra check.

The mood of the audience always makes a difference in the energy of the performers. When we can tell that an audience is enthusiastic, it makes us more energetic and excited. When an audience is quiet, we still give them our best, but it is much harder work and much less fun. Sometimes an audience will surprise us by being very subdued during the show, and then giving us a huge ovation at the curtain call.

Part VII - Intermission

The backstage of the Broadway Theatre goes straight up and down. The women's dressing room is on the fourth floor. In the course of one show I have to go to the stage and back to the dressing room several times, which means I probably climb about 30 flights every show! On two-show days I feel like I have been on the Stairmaster. The cast has all been commenting that after all those flights of stairs, we look pretty good from behind!

On Wednesdays and Saturdays we have a matinee and an evening show. Most of the principals are double- or triple-cast, so they never have to do more than one show a day. The exceptions are Daniel Webb, who plays Colline, and Daniel Okulitch, who plays Schaunard. Those two guys do all eight shows a week, unless by chance they are sick. Daniel Webb did over one hundred performances before he finally caught the "Bohème Bug," and was too sick to perform. The "Bohème Bug" is a twenty-four hour stomach flu that has struck the majority of the cast at some point over the last month. Just when we think we have finally beaten the Bug, somebody else comes down with it and has to stay home from the show.

It is always a dilemma how to spend the three hours between shows on Wednesdays and Saturdays. I am lucky that I live on the Upper West Side, so I can go home and make dinner or even take a nap, but some of the cast commutes in from New Jersey or Upstate New York, and have to find a way to fill the time. Many people have a leisurely dinner in the Theater District, go to the gym, shop, or lie down on the floor in the dressing room to try and get a little sleep.

Almost everyone in the cast has some free time backstage while the performance is in progress. I like to read or study some music that I am working on at my voice lessons, although sometimes it is fun just to gossip with the other women in the dressing room. Many people catch up on calls on their cell phones, and there is usually a fierce card game in the hallway. Sometimes on Saturday afternoons we listen to the radio in the men's dressing room if there is a broadcast from the Metropolitan Opera.

We do not have the luxury of a lot of space backstage. There isn't really a Green Room. What we call the Green Room is just a table with some folding chairs in the basement. In spite of the small space, the cast keeps the "Green Room" stocked with chocolate and fruit. Usually around once a week someone will bake some cookies to share. It is forbidden to eat while we are in costume, although a cookie now and then sometimes slips by unnoticed!

On any given night there are usually a handful of Bohème cast members who go out together for a beer or margarita. Sometimes there is a large group if someone is celebrating a birthday. Recently, some of us went salsa dancing down in the East Village to celebrate the birthday of the assistant director, Heidi Marshall, but mostly we stay in the Theater District. After attending a Sunday matinee in January, movie star Jim Carrey came backstage to meet the cast and then came out for beers with us!

Every once in a while there is a Question and Answer session with the audience after the show. February 4th was Kids Night at La Bohème, complete with an autograph signing for the children and an early curtain time. In general, the cast is very generous about donating their time to special events. Many of us have participated in benefit concerts for various organizations on our own time, and as a cast, we performed a benefit for the Robin Hood Foundation. Sometime in the next few months we will do an extra performance to benefit The Actors' Fund. I recently attended The Actors' Fund performance of Hairspray. It was a fantastic performance, with an especially enthusiastic audience, as many of us watching are members of other Broadway shows.

January was a particularly tough month for Broadway. The months following Christmas are always difficult because tourism is down after the holidays and many Broadway shows are forced to close. Even though Bohème is surviving the audience slowdown, there are nights when we have several empty rows of seats in the balcony. One would be surprised how easy it is to get a seat this time of year at any of the hit shows. In February, on a Wednesday matinee or a Tuesday or Wednesday night, it is possible to walk up to the box office and immediately buy a ticket. This won't be the case for much longer, however! Tourism picks up in the spring, and with the Tony Awards coming up, I predict it will be nearly impossible to get a ticket for La Bohème until at least September 2003.

Paintings by Maria Sibylla Merian, artist and scientist (1641-1712).

Besides creating visual images of great beauty, Maria Sibylla Merian made observations that revolutionized both botany and zoology. This extraordinary artist-scientist was born in Frankfurt, Germany. Her father, Matthäus Merian the Elder, was a Swiss printmaker and publisher who died when she was three. One year later her mother married Jacob Marell, a Flemish flower painter and one of Merian's first teachers.

From early childhood, Merian was interested in drawing the animals and plants she saw around her. In 1670, five years after her marriage to the painter Johann Andreas Graff, the family moved to Nuremberg, where Merian published her first illustrated books. In preparation for a catalogue of European moths, butterflies, and other insects, Merian collected, raised, and observed the living insects, rather than working from preserved specimens, as was the norm.

In 1685 Merian left Nuremberg and her husband to live with her two daughters and her mother in the Dutch province of West Friesland. After her mother's death, Merian moved to Amsterdam. Eight years later, at the age of 52, Merian took the astonishing step of embarking-with her younger daughter-on a dangerous, three-month trip to the Dutch colony of Surinam. Having seen some of the dried specimens of animals and plants that were popular with European collectors, Merian wanted to study them in their natural habitat. She spent the next two years studying and drawing the indigenous flora and fauna. Forced home by malaria, Merian published her most significant book in 1705 - Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam, which established her international reputation.

|

The Many Voices of the Poet Ai

by Pat Harrison

The Radcliff Quarterly, Spring 2000 |

|

|

In this age of multiculturalism, when so many writers are exploring their ethnic identity, the poet Ai B '76--who is half Japanese, as well as African American and Native American--defies the times by assuming a myriad of other identities and voices, none expressly her own. Ai's six volumes of poetry, which began appearing in 1973 and culminated last year in a major collection of new and selected poems, feature dramatic monologues by people whose voices don't usually make it into literature: a child-beater, a rapist, a self-abortionist. She has also written in the persona of public figures as diverse as J. Edgar Hoover, Marilyn Monroe, and Mary Jo Kopechne. But until recently, when Ai began work on a memoir, she had not written directly about her own background in what she's described as a "half-breed culture" in Tucson.

"I like making up characters," Ai told the Quarterly in a recent phone interview. "Writing the monologue has afforded me that opportunity, but I really kind of fell into it. My first poetry teacher said that the first person is often the strongest, and that seemed to be my gift. I just did it so well that every poem I wrote in the first person seemed to be a success, whereas others weren't. So I did it over and over, and by the second year of graduate school, I was firmly on that path. I find it very exciting to become other people. I don't think of them as masks for myself. Some people say that, but to me they're not. They're my characters; they're not me."

Inspiration for her monologues comes from diverse sources, including late-night television. "For my Jimmy Hoffa poem," Ai said, "I was watching Johnny Carson one night and he told a joke. 'Who did they find under Tammy Fay Baker's makeup?' The answer was Jimmy Hoffa. And I said to myself, 'I want to write a poem about Jimmy Hoffa.'"

More recently, she's been writing a cycle of poems about the race riot that occurred in Tulsa in 1921, when the Greenwood section of the city, known as the black Wall Street, was set afire by white men and boys. "I was watching Nightline," Ai reported, "and one of the survivors said there was so much smoke and fire that his sister said, 'Brother, is the world on fire?' That line got me into my poems."

From the beginning of her career, publication has come easily to Ai, perhaps in part because her poetry is so accessible. As an undergraduate at the University of Arizona, she met her mentor, New York University Professor Galway Kinnell, when he came to campus to read. After the reading, Ai began sending her poetry to Kinnell for his comments, and he encouraged her to apply to the writing program at the University of California at Irvine. During her second year at Irvine, Kinnell took a copy of Ai's thesis to an editor at Houghton Mifflin, and in 1973, her first book, Cruelty, appeared. It was after Cruelty came out that Ai was awarded her Bunting fellowship, which she held in 1975-76. Five additional books followed: Killing Floor (1979), Sin (1986), Fate (1991), Greed (1993), and Vice (1999), all published by Houghton Mifflin except the last two, which Norton brought out.

The titles of Ai's books indicate the gritty content of her poems. Listen, for example, to the opening lines of "The Cockfighter's Daughter," from her book Fate: "I found my father,/face down, in his homemade chili /and had to hit the bowl/with a hammer to get it off,/then scrape the pinto beans/and chunks of ground beef/off his face with a knife." Some critics have accused the poet of sensationalism, while others have lauded her risk-taking. Whatever the critics think, though, Ai's books have always done well with readers, selling better than poetry usually does.

"I decided to go the Wordsworthian way when I was in grad school," Ai said, "and write in the language of the common man. I don't know if I succeeded, but that was one of my goals. I made my work as accessible as I could, without compromising my intelligence."

Ai's plain speaking has certainly earned her a share of prizes. In addition to her Bunting fellowship, she has won a Guggenheim fellowship, the Lamont Prize, an American Book Award, and, most recently, for Vice: New and Selected Poems (Norton, 1999), the life-changing National Book Award. Before this latest award, Ai was a visiting professor at Oklahoma State University, a position similar to the many teaching appointments she's held throughout her career. But last fall, on her return to Stillwater from accepting the award in New York, OSU offered her tenure as a full professor. "The financial security that I have wanted my whole career I now have. It was almost too much for me. I had wanted it for so long."

Now comfortably ensconced at OSU, Ai is conducting research for her memoir, looking up relatives who were members of the Choctaw and Southern Cheyenne tribes in Oklahoma. One of the next voices we hear from the poet Ai will likely reflect her own rich history, including details about that Tucson "half-breed" culture.

Ai's first book, Cruelty, received critical acclaim when it was published in 1973. Her second book, Killing Floor, was the 1978 Lamont Poetry Selection of the Academy of American Poets. Her next book, Sin (1987), won an American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation and was followed by Fate in 1991. In 1999 Vice was the winner of the National Book Award for Poetry. Ai is a native of the American Southwest and lives in Tucson, Arizona. In the year 2002-2003 she will hold the Mitte Chair in Creative Writing at Southwest Texas State University.

|

JIM LEHRER: The National Book awards were announced last night in New York. Awards were given for poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and children's literature. Elizabeth Farnsworth begins a series of conversations with the winning authors.

ELIZABETH FARNSWORTH: The winner for poetry this year is known as Ai, a Japanese word meaning "love." She won the award for Vice, a book of new and selected poems, many of them dramatic monologues. Born in 1947 in Albany, Texas, Ai published her first book in 1973. She currently teaches poetry and fiction at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater. Thanks for being with us, and congratulations. ELIZABETH FARNSWORTH: The winner for poetry this year is known as Ai, a Japanese word meaning "love." She won the award for Vice, a book of new and selected poems, many of them dramatic monologues. Born in 1947 in Albany, Texas, Ai published her first book in 1973. She currently teaches poetry and fiction at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater. Thanks for being with us, and congratulations.

AI, National Book Award, Poetry: Oh, thank you, and you're welcome. |

|

|

Tough topics for poetry |

|

ELIZABETH FARNSWORTH: I'm struck by the tough topics you take on. You deal with child abuse, murder, necrophilia, torture. What draws you to these topics? ELIZABETH FARNSWORTH: I'm struck by the tough topics you take on. You deal with child abuse, murder, necrophilia, torture. What draws you to these topics?

AI: Well, it's really the characters, because I write monologues. So when I find an interesting character, I usually start that way. I'll think of somebody who interests me, and then fill in the blanks, so to speak. So it's sort of happenstance in a weird way, you know. It's just sort of... I'm sort of constructing these lives. But I tend to like scoundrels. I like to write about scoundrels because they are more rounded characters in some respects than a really good person. You know, there's a lot more to talk about with the scoundrels.

ELIZABETH FARNSWORTH: And, why the dramatic monologue form?